What's Happening Archive

The 2021 West Coast Ocean Acidification (WCOA) cruise aimed to better understand how changing ocean chemistry affects marine communities along the U.S. West Coast, from Mexico to Canada. As part of this effort, researchers used plankton tows to capture detailed snapshots of phytoplankton and zooplankton species and their diversity. The Ocean Molecular Ecology (OME) group, in partnership with the Carbon Group, is working to compare these traditional plankton collections with environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling. This comparison is helping validate the use of eDNA for future ocean monitoring efforts.

To start this process, UW undergraduates Mugdha Chiplunkar and Karina Lai spent several weeks inventorying the extensive collection of preserved plankton samples from the cruise. They cataloged each sample in a spreadsheet, recording collection details (like date and location) and taking photos of each container from multiple angles. This organized inventory made the samples more easily accessible, as it was faster to locate and reference individual samples without having to dig through the entire storage cabinet.

The next phase involved carefully removing a small volume of ethanol, the preservative in the jars, from each sample. This ethanol contains traces of DNA from the organisms in the sample, so filtering and analyzing it can reveal information about community composition. The process wasn’t always easy; some jars were packed with plankton, which made drawing out the ethanol a slow and tricky task.

To estimate the volume of plankton in each jar, Mugdha and Karina, alongside OME researcher Shannon Brown, used weight displacement. First, they estimated the total volume of the ethanol and plankton together using a graduated cylinder. Then, the contents were poured through a sieve to collect the liquid separately from the plankton. Subtracting the liquid volume from the total volume helped them estimate the volume of the plankton only. This process was time-consuming and required a lot of stirring, especially when larger plankton slowed the draining process. Transferring samples was also messy which required extensive sterilization and definitely left the lab smelling distinctly of preserved plankton for days.

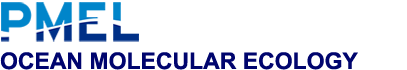

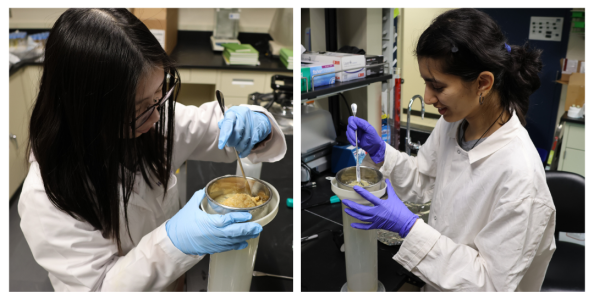

Karina Lai & Mugdha Chiplunkar busy at work during the weight displacement step

After volume estimation, the team took the previous aliquoted ethanol and filtered over 150 ethanol samples onto disc filters over the course of three days. These filters were then processed for DNA extraction, PCR-amplified for target genetic markers, and sent out for sequencing. In parallel, OME also extracted DNA directly from the plankton subsamples taken from the jars themselves. This provided an additional comparison point in the study.

Though labor-intensive, this work provided Mugdha and Karina with valuable hands-on experience in marine sampling, molecular techniques, and ecological research. Along the way, they encountered a fascinating array of plankton, and even discovered a few tiny squid hiding among the samples. Their efforts are helping NOAA and the OME team advance the use of eDNA to monitor the ocean’s changing ecosystems.

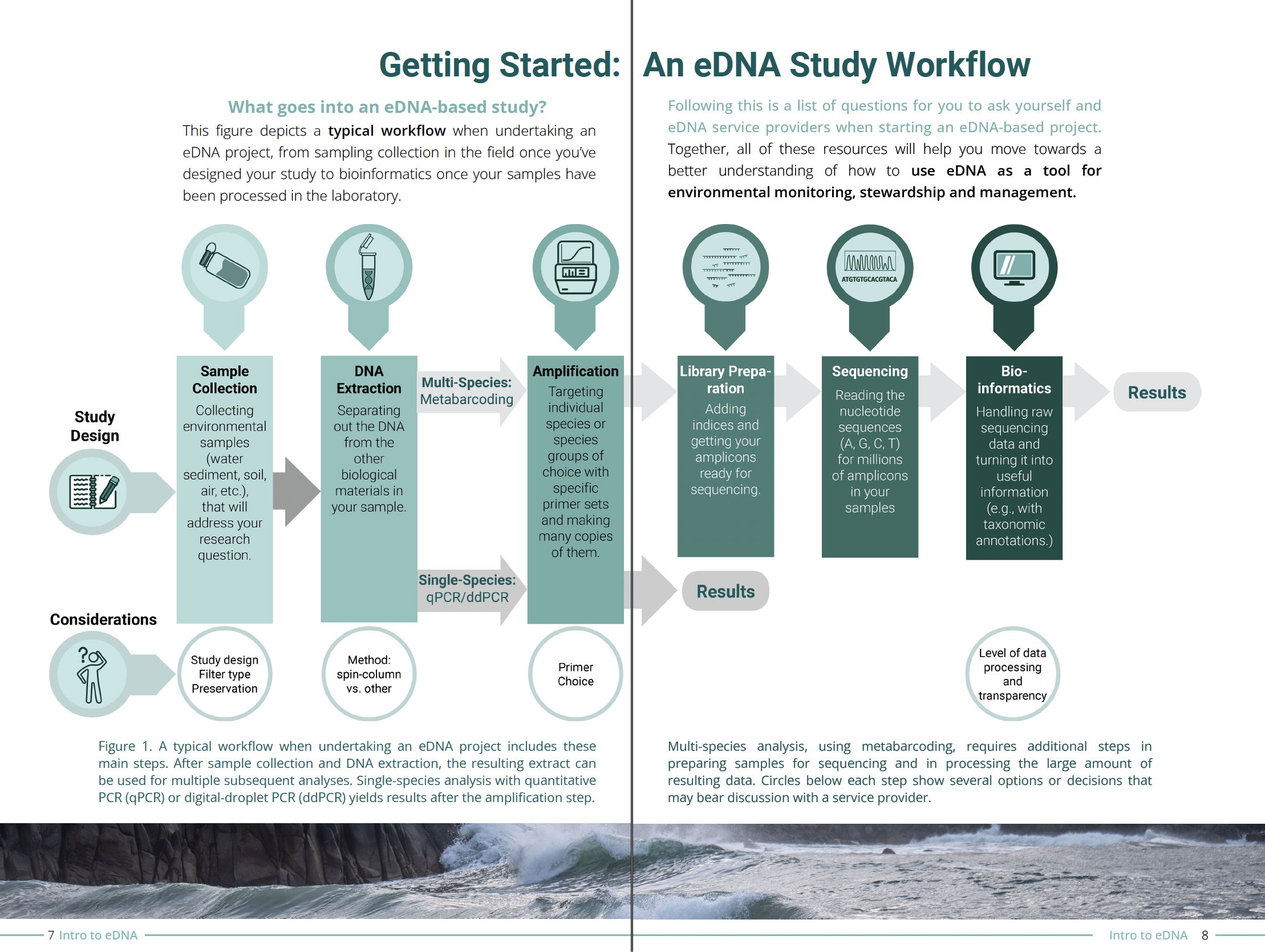

Environmental DNA - or eDNA - is, simply put, DNA that can be found in the environment, such as soil, sediment, water, and air. Organisms are constantly shedding parts of themselves - such as dead skin, mucous, or waste - into their surroundings. The DNA in this shed organic matter, along with organismal DNA from microscopic organisms such as protists and bacteria, makes up eDNA. When a sample of water is collected, scientists can analyze the eDNA within it to determine what species are or were recently present in those waters, even if those species are not observed with the naked eye.

The use of eDNA is becoming increasingly popular across the world, including in the Northeast Pacific Ocean region. Approaches to collect and detect eDNA are now providing rapid, accurate, and cost-effective means of identifying marine organisms - from marine mammals to fish, invertebrates, and harmful algal blooms - and are being used to build valuable baselines for marine biodiversity datasets. Despite the growing evidence of eDNA’s effectiveness in answering a wide range of research questions, its application in environmental management is still evolving.

There are many possible applications of eDNA to marine monitoring and management, including Marine Protected Area (MPA) and Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) monitoring and management; threatened species detection; invasive species detection; and environmental restoration. As marine managers and stewards gain a better understanding of eDNA technology, and as scientists learn more about community needs, this powerful tool will continue to become more effective for environmental management

Whether you’re a marine steward or manager who is new to eDNA or someone already familiar with the technology but eager to learn more, this ‘eDNA primer’ is designed to deepen your understanding of this innovative tool. This resource was developed based on community responses from the Mobilizing eDNA for Management in the Northeast Pacific webinar and workshop, as well as the related Using Environmental DNA for Monitoring and Stewardship in the NE Pacific webinar.

Partners: eDNA Collaborative, Hakai Institute, The Ocean Decade Collaborative Centre for the Northeast Pacific, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), NOAA ‘Omics, and McGill University’s Sunday Lab

As part of the Ocean Molecular Ecology (OME) group’s effort to optimize eDNA collection techniques and broaden our sample collection capabilities at sea, we are conducting a study to compare a new filter produced by an American small business, the Smith-Root self preserving eDNA filter to our current filter, the Millipore sterivex capsule filter. The collection and filtration of eDNA samples at sea is limited in part by the technical skills required to filter and preserve these sensitive samples without contamination. With our current filter, the flammable preservative and low-temperature storage requirements also present a barrier to shipping and sample storage in some field applications.

The self-preserving filter, developed by a small business in Vancouver WA, is designed to capture and preserve eDNA from multicellular organisms. It has been found to perform as well as ethanol-based preservation for a 6 month period. Rather than a preservative, the Smith-Root filter utilizes a proprietary desiccating filter housing to preserve captured DNA and cells, eliminating the need for chemical preservatives. This design simplifies operation, requires less training, and streamlines shipping. However, these filters have not been tested against the sterivex filter, nor have they been tested on their ability to capture DNA from single-celled organisms. Our current study aims to address these gaps by testing the sterivex head-to-head against the Smith-Root filter using the same filter material and pore size.

For this study, Han Weinrich and Zack Gold collected water samples from local fresh and seawater sources alongside water from the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, then they filtered them in the lab - half with sterivex filters and half with the Smith-Root filters. To avoid any degradation of DNA before preservation, Han and Zack filtered the samples immediately after collection, resulting in several 12 hour days. DNA extractions at six time points, from one day to six months post-collection, will assess the preservation performance of the Smith-Root filter relative to the sterivex filter. Preliminary results from extractions conducted up to three months post-collection indicate that the Smith-Root filter preserves DNA comparably to the sterivex filter. Further analyzes will include sequencing the extractions to determine if both filters capture and preserve the same organisms at the same proportions - a critical metric for the OME as we aim to capture biodiversity at all levels of the ecosystem, from bacteria to whales.

If the Smith-Root filters perform comparably to the sterivex in meeting OME's eDNA objectives, they may offer an alternative to sterivex filters in certain field applications - saving time and space on research vessels while enabling eDNA monitoring in a broader range of environments. In addition, the National Aquatic eDNA Strategy seeks to advance eDNA sampling technologies by developing low-cost, high fidelity devices to enable large-scale collection. The Smith-Root filter could be employed in the development of a new eDNA sampler.

Since 2020, the Ocean Molecular Ecology (OME) group has collaborated with Ecosystem and Fisheries Oceanography Coordinated Investigations (EcoFOCI) to maintain a seawater environmental DNA (eDNA) time series in the U.S. Arctic. This fall, Shannon Brown participated in the annual EcoFOCI Fall Mooring cruise, which focuses on deploying and recovering oceanographic moorings and collecting shipboard biophysical samples at and between mooring locations. U.S. Arctic marine ecosystems are rapidly changing in response to climate change with accelerating ocean warming and sea ice loss leading to cascading ecosystem effects. OME leverages eDNA approaches to examine the regional biodiversity of microbes, phytoplankton, zooplankton, fishes, and mammals. By pairing eDNA analyses with physical and chemical measurements, these efforts establish critical baselines that support fisheries management and marine conservation. Additionally, in collaboration with the FWC Center for Red Tide Research, our eDNA samples contribute to studying harmful algal blooms (HABs), which can affect marine life and human industries in the region.

During this cruise, Shannon successfully filtered 110 eDNA samples collected from CTD Niskin bottles. The team also deployed an autonomous eDNA sampler at the M2 mooring site. Designed to collect samples biweekly for a year, this sampler had previously been deployed in the Chukchi Sea, where it successfully gathered 24 samples from September 2023 to July 2024. It was recovered in August by the RV Sikuliaq and immediately shipped from Nome, AK to Dutch Harbor, AK, to meet the Fall Mooring cruise.

Monitoring in the Arctic is challenging given its remoteness and the difficulty of navigating harsh sea ice and ocean conditions, making it impossible to manually sample for half the year. Autonomous eDNA samplers are an innovative solution, enabling year-round biodiversity sampling. Due to a limited number of samples and only a few deployment opportunities, we decided to collect one unit, turn it around in the field, and redeploy it for another year.

Redeploying the autonomous sampler highlighted the logistical complexity of Arctic fieldwork. Alaska, the largest U.S. state, lacks road connections between key locations like Nome and Dutch Harbor, requiring equipment to be transported by plane or boat. With only a week between cruises, the team opted to ship the sampler by air—a process fraught with delays. Unfortunately, after countless hours spent coordinating the unit transfer, the sampler missed the departure of the NOAA Ship Oscar Dyson departure date. Fortunately, Han Weinrich was still on the island and ready to receive the delayed unit. A few days after departing, the NOAA Ship Oscar Dyson returned briefly to Dutch Harbor, and the amazing crew retrieved the sampler with a small boat.

Once aboard, Shannon and the EcoFOCI team worked tirelessly to prepare the sampler for deployment within 48 hours. When a malfunction caused the unit to power down spontaneously, Shannon spent hours disassembling and reassembling components to diagnose the issue. With the help of Oscar Dyson’s Chief Engineer (a true MacGyver), foam ear plugs, and some new springs, a solution was found just three hours before the unit was successfully deployed!

Sadly, the sampler was prematurely recovered by a fishing vessel on November 24, just 11 weeks after redeployment. While it’s unclear if any samples were collected, the incident underscores the unpredictable nature of field research in the Arctic. Despite these challenges, this mission highlights the resilience and ingenuity of the scientific team. The data collected through these efforts will inform the sustainable management of Arctic marine ecosystems and improve our understanding of biodiversity in this rapidly changing region. Thanks to the crew of the NOAA Ship Oscar Dyson and the entire science party for a successful cruise!

Shannon Brown preparing an autonomous eDNA sampler for deployment on the NOAA Oscar Dyson. Credit: Mabel Baldwin-Schaeffer/NOAA Fisheries

The Phycological Society of America’s (PSA) joint meeting with the International Society of Protistology (ISOP) and International Society for Evolutionary Protistology (ISEP) brought together algae, phytoplankton and protist researchers from across the globe. During the meeting, research from carbon dioxide draw-down with kelp farms to important evolutionary questions of protists in the tree of life were presented to an international audience of academic, federal, state, and local government scientists.

Sam Setta presented on phytoplankton changes with temperature and acidification from the West Coast Ocean Acidification (WCOA) 2021 Cruise. During the meeting, Sam had the opportunity to connect with many scientists, including researchers from the Washington Department of Natural Resources and Shannon Point Marine Center at Western Washington University.

Following the conference, Sam flew to Savannah, Georgia for Dr. Holly Bik’s workshop “Telling Stories Through Data”. Unfortunately for workshop participants, this happened to coincide with Hurricane Debby’s arrival on the U.S. East Coast. While the workshop was originally planned to take place on Sapelo Island, evacuation orders meant the location changed to downtown Savannah, GA.

During the workshop (and Hurricane Debby), Sam learned new data visualization methods and best practices. In the afternoon sessions, Dr. Virginia Schutte led the group in a science communication component. Sam and workshop participants explored a variety of science communication platforms and best practices and brainstormed a future science communication plan. Graduate students to early career researchers participated in the workshop and learned data visualization and storytelling from each other while forming a community to rely on for tips and advice on “Telling Stories Through Data” in the future.

Through these two great experiences this summer, Sam was able to communicate with scientists on findings from the West Coast Ocean Acidification cruise, meet scientists with similar research, learn data visualization and science communication, and meet a wonderful group of early career researchers.

My name is Ella Crotty, and I am an undergraduate research intern through the NOAA Ernest F. Hollings Scholarship Program. I chose to work with OME for my internship because I didn't know very much about environmental DNA (eDNA), and I wanted to learn! eDNA refers to genetic material that organisms leave behind in the environment by shedding skin, releasing mucus, etc. It can be used to detect if species are present in an area of the ocean using a water sample. For my project, I worked with an automated sampler that sits in the water and collects eDNA samples at regular intervals by filtering water samples through super-fine filters.

My internship included fieldwork in the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary (OCNMS). I went out to the northwest coast of Washington twice to help with sampler recovery and redeployment. I helped collect and filter eDNA samples on the boat, then after the sampler was recovered, I helped store the samples from the sampler, which had already been filtered underwater. We returned to land and spent a day sterilizing the sampler before redeploying it, which was a complicated process. I had never worked with such a big and complicated instrument before, and it was interesting to learn about the logistics of setting up and maintaining something like that without access to a full lab! We brought a lot of tools and extra parts, in case anything broke and needed to be fixed on the coast between boat days.

The main goal of my research project was to determine how the presence of different species in OCNMS changes when the amount of oxygen in the water is low. Low oxygen, also known as hypoxia, can cause stress and death in marine animals. Two mg/L of oxygen is often used as the upper limit of what counts as hypoxic. I compared the data from our eDNA samples, which told me which species were detected in the sanctuary on certain dates, with dissolved oxygen data sampled from CTD casts and moorings. In OCNMS during the summer, a process called coastal upwelling causes oxygen-poor deep water to move up from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, which decreases oxygen levels near the coast. However, some species are more sensitive than others, and some, like larger fish, are mobile and can move away from the low-oxygen areas. So, our main research question was: which species stick around when the oxygen drops, and which can no longer be detected? This question will help us understand how seasonal changes in oxygen are impacting OCNMS waters.

It required quite a few stages of data analysis and quality-checking in order to make the environmental data and eDNA data compatible with each other. Using the programming language R, I cleaned the data and matched the species detections to the temperature and oxygen at the date and time when the eDNA samples were taken. I implemented a lot of checkpoints to ensure that the code was doing what I wanted it to. For example, I checked to make sure that everything was in the same time zone, but between the CTDs, mooring, eDNA sampler, and handwritten sample data, I had to be very vigilant about converting the time zones before combining data.

First, I focused on species that OCNMS and the coastal treaty tribes consider high priority for monitoring and management and that were detected at least 10 times. Of the 64 priority species, we detected 24 and four were detected at least 10 times. The two species with the most detection data were Pacific herring and the copepod Acartia longiremis. I didn't find any correlation between oxygen levels and the presence of these species, which suggests that seasonal hypoxia is not impacting these commonly detected taxa. Herring are known to be pretty hypoxia-tolerant, which agrees with my findings. I also investigated species outside the priority list by calculating a bunch of statistics and filtering for significant results. I found a few species that did have observable relationships with hypoxia, including two species of copepod, tiny crustaceans that are used as indicators of ecosystem health. Through this internship, I developed a code workflow that combines environmental data with eDNA data, which is useful as we continue to study how different species are affected by environmental conditions.

As the Ocean Molecular Ecology (OME) group works to make our science and lab practices open and accessible, we have prioritized standardizing and sharing our environmental DNA sample collection and processing protocols to a public repository. The Better Biomolecular Ocean Practices (BeBOP), a U.N. Decade Endorsed project under Ocean Biomolecular Observing Network (OBON), pioneered a Minimum Information about an Omics Protocol (MIOP) format to better compare practices and integrate data generated when studying ocean life. BeBOP formatted protocols are accessible, detailed, traceable, machine-readable, and standardized. Importantly, they are designed to provide the reader with all the information needed to replicate a protocol from supplies purchasing and troubleshooting to the method background and a step-by-step procedure.

In the last four years, OME has collected over 2,800 eDNA samples from coastal stations off the western coast of North America in the Northeastern Pacific Ocean, Bering Sea, and Arctic Ocean. Since 2023, we’ve extracted over 1,200 samples and sequenced/processed over a thousand. As we pushed through our backlog, we fine-tuned our standard operating procedures for all in-house lab work, including eDNA collection, extraction, and PCR amplification. Our published protocols are written for reproducibility so a new lab could replicate our efforts. We aim to continue our efforts to encompass all field and lab protocols performed by OME over the next year. These protocols are archived, version-controlled, and citable in Zenodo repositories.

One major challenge of studying marine and aquatic ecosystems is obtaining an accurate map of the type and number of species within the environment. The United States is home to a wide range of aquatic ecosystems, including estuaries, lakes, and oceans with one of the largest exclusive economic zones in the world. Biodiversity drives the health, functioning, and services provided by freshwater and marine ecosystems and has substantial cultural and economic significance, making accurate maps of biodiversity so important. Advancements in biomolecular technology now allow scientists to detect DNA shed by marine life into the water, a technique called environmental DNA (eDNA). eDNA approaches provide a powerful, non-destructive, and cost effective tool that gives us the ability to monitor life in our marine and aquatic environments.

The White House Office of Science, Technology, and Policy (OSTP) recognized the power of this tool and the importance of studying ecosystem biodiversity across the nation with the release of the 'National Strategy for Aquatic Environmental DNA' as part of a larger OSTP effort to advance sustainable ocean management. This strategy empowers federal agencies and partners to effectively harness eDNA as a detection tool for mapping and monitoring biodiversity. It also calls other public and private agencies to action as we work to unite science and entrepreneurial efforts to collaboratively improve the eDNA research and operations space. Importantly, NOAA has been leading the research and development of eDNA tools for the past decade to transition to operational marine biodiversity monitoring.

For the past 7 years, the Ocean Molecular Ecology (OME) Program at PMEL has been employing eDNA to study coastal ecosystems along the U.S. West Coast as well as the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean. This national strategy is a call to action for continuing our efforts to develop and implement eDNA tools to monitor marine biodiversity at scale. In particular the strategy highlights the need for OME’s work to standardized, reproducible eDNA sampling practices, improve and deploy autonomous eDNA samplers, and fill eDNA reference databases. OME will continue to invest in the research, development, and application of eDNA science within NOAA in support of key agency missions from harmful algal bloom monitoring to protected species management to climate resilient fisheries and ecosystem management.

Read more about White House strategy to capitalize on the immense power of eDNA at NOAA Research.

Over 62 scientists from PMEL, including researchers from NOAA’s Cooperative Institutes and the University of Washington's Cooperative Institute for Climate, Ocean, & Ecosystem Studies (CICOES) and Oregon State University's Cooperative Institute for Marine Resources Studies (CIMRS) attended the Ocean Sciences Meeting in New Orleans from February 18-23. The 2024 Ocean Sciences Meeting served as a conference that unified the ocean community and brought researchers together to share findings, make connections, and advance science. Five members of the Ocean Molecular Ecology group were in attendance.

Sean McAllister presented results from the 2021 West Coast Ocean Acidification (WCOA) Cruise, which was in collaboration with PMEL Ocean Carbon. During the cruise, 525 unique environmental DNA (eDNA) samples were collected from Vancouver Island, BC to Southern California. Our eDNA samples captured diverse marine communities (e.g., phytoplankton, fish, marine mammals) across a large spatial gradient. When analyzed alongside chemical and physical parameters, we were able to draw preliminary conclusions regarding community structure in relation to warming, ocean acidification, and low-oxygen events (hypoxia) along this expansive spatial gradient. Further analysis is underway to identify key indicator species for use in monitoring and predicting ecosystem health in our changing oceans.

Shannon Brown presented on ongoing research with autonomous eDNA samplers in the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary. Changing ocean conditions, driven by climate change, are threatening the sanctuary’s marine ecosystem with increased, hypoxic events. We deployed samplers alongside oceanographic moorings to better understand how marine communities are impacted by these changing conditions. Our results captured a wide range of taxonomic diversity including species of commercial, recreational, cultural, and subsistence importance.

Zack Gold co-chaired a session on Ocean Biomolecular Observing Networks, and presented on a cross-NOAA bioinformatics effort to improve trustworthiness and reliability of eDNA data. More specifically, he outlined a suite of tools and approaches to accurately assign taxonomy when processing eDNA data to better characterize marine biodiversity. Han Weinrich presented on their honors thesis work investigating microbial prokaryotic communities associated with hydrothermal vent tube worms. Sam Setta presented on her PhD thesis work on diatom distribution and diatom diazotroph associations across nutrient regimes.

My name is Nicholas Silverson, and I am a master’s student at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. My research, funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) INTERN program and Graduate Research Fellowship (GRF), as well as the Distributed Biological Observatory (DBO), focuses on the biodiversity, community, and population structure of ocean floor animals (benthic macrofauna) in the Pacific Arctic. As part of my project, I visited NOAA PMEL and worked alongside Matthew Galaska, a principal investigator in the PMEL Ocean Molecular Ecology (OME) group, to incorporate a genomics approach to questions of biodiversity and population structure.

I had the chance to participate in two research cruises off the coast of Alaska this past summer on the Sir Wilfrid Laurier, a Canadian Coast Guard ice-capable buoy tender, and the research vessel Sikuliaq, owned by NSF. They were truly incredible experiences; in addition to witnessing enormous flocks of seabirds, pods of whales, and the aurora, I was able to engage with scientists studying this region so affected by climate change. I worked with Matthew Galaska and my thesis advisors, Jacqueline Grebmeier and Lee Cooper, to design a sampling protocol and sampled sites in the DBO, which consists of observation sites from the northern Bering to the Beaufort Seas that document and evaluate biological changes at productive hot spots. With members of my lab group, I collected a broad range of benthic macrofauna specimens and preserved them in ethanol for later study at PMEL. We are aiming to publish underrepresented cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) barcodes to the National Nucleotide Database (NCBI), which will aid other studies in the accurate identification of organisms. Additionally, for two dominant clam species (Bivalvia) and a marine worm (Polychaeta), I collected 8-15 individuals to analyze their population structure and unravel any potential open ocean barriers to dispersal between Southern (Bering Sea) and Northern (Chukchi Sea) populations. This data will complement the analysis of long-term biodiversity and environmental data collected as a part of the DBO.

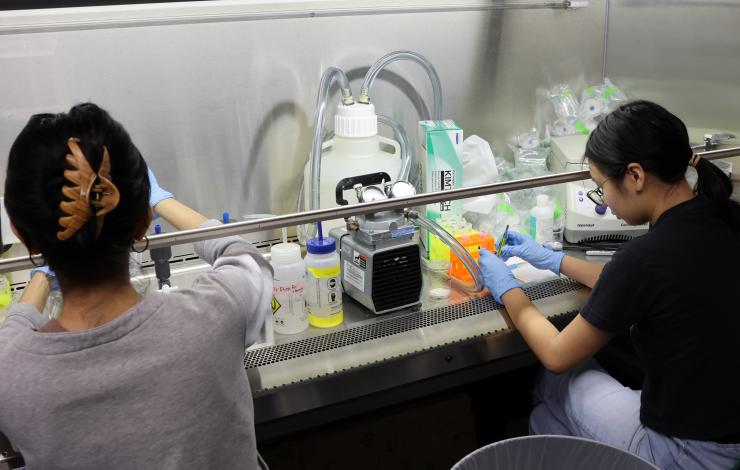

I spent two weeks at PMEL this past December learning the methodology for DNA extraction and PCR amplification. DNA barcoding of conserved regions of mitochondrial DNA can provide accurate identifications of animals and give insights into barriers to gene flow that morphological study alone cannot provide. Despite some early challenges with low DNA quantities, we successfully extracted DNA from 120 benthic animals and amplified their DNA using a COI primer set. The DNA will be Sanger sequenced this winter, and I’ll return to PMEL for another two weeks to bioinformatically process the data and perform the associated analyses. These data will contribute to understanding how ocean floor communities are changing with warming waters and reduced sea ice, which impacts primary production and energy flow in these seasonally productive ecosystems. My experience at PMEL will form an important part of my master’s program and has been fundamental to my growth as a scientist as I have been learning important methodologies for understanding community structure and change.